世界に誇る日本の「文様」

〜友禅が導く原点回帰〜

Japanese monyo: auniversal art form and the envy of the world

- A return to its origin guded by yuzen -

MORIGUCHI KUNIHIKO

森口邦彦の手仕事

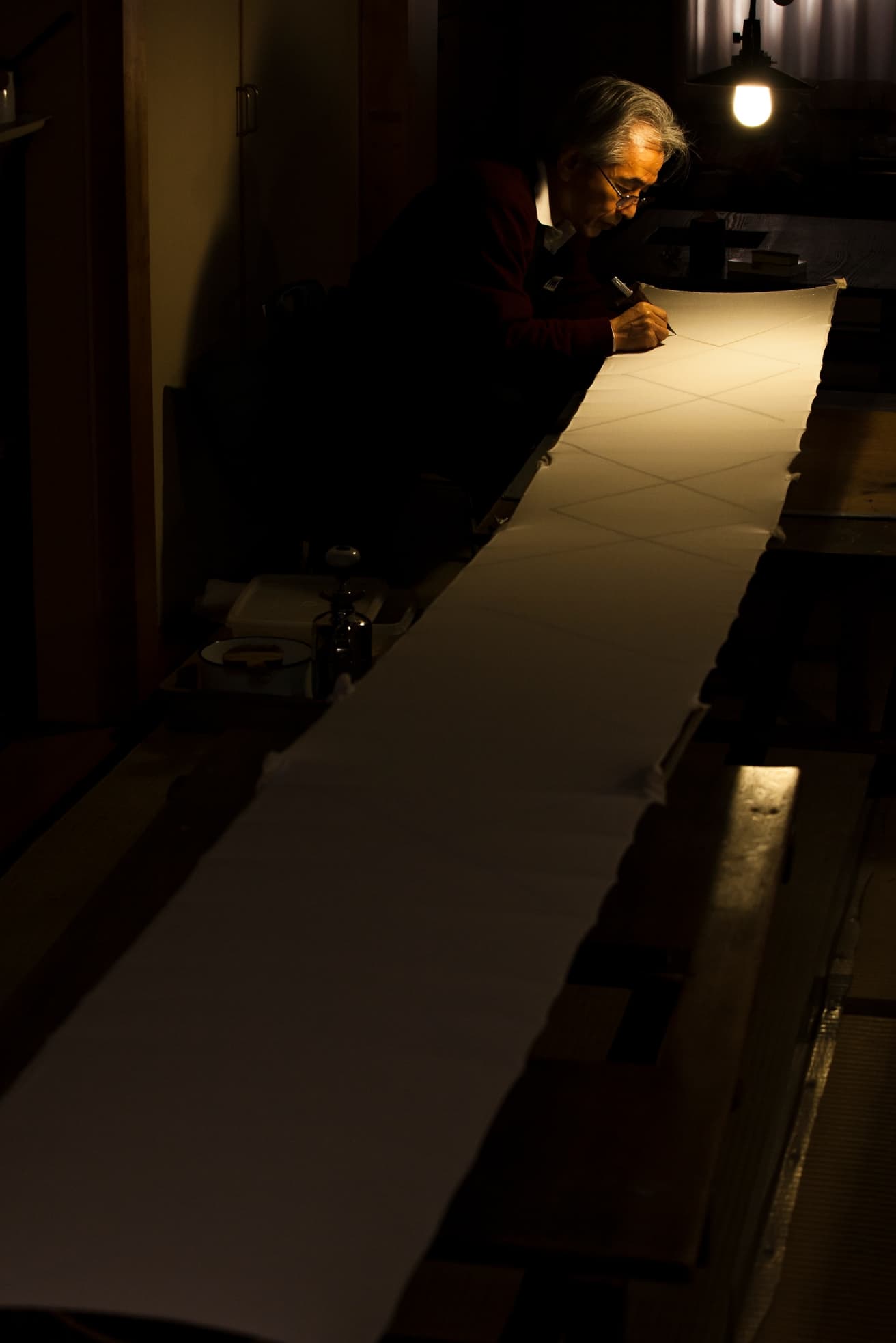

溶けかけの雪。どこか懐かしさを感じる温かい香り。糊の香りかもしれない。風情ある京都のご自宅で、森口邦彦氏は淡々と筆を動かしていた。こちらが息をひそめてしまうくらい、静かで孤独な作業だ。ただそこには何かしら心地よい集中力が漂う。草稿から下絵に移ると、何本もの定規を用い、スケッチブックのデザインを生地に再現する。下絵というより緻密な作業。中腰になって小気味よいステップを踏んで筆をおろす。糊置きは、筒に入った糊を下絵に沿って引いていく。まるで時間が止まってしまったかのような深い集中力が伝わってくる。ふと見回せば何本もの筆が並んでいた。それらの筆を駆使して糊の間に色を挿す。とても丁寧でなめらかな筆遣い。そして、美しい色遣いに邦彦氏の感性を感じ取る。同じ藍でもひと筆ひと筆違う藍にみえてくるのは興味深い。最後に邦彦氏は文様の初期の設計図を見せてくれた。文様が完成するまでの物語は挑戦の繰り返しである。深い探究心と底知れぬ創造力をもって文様の可能性を探る。そう、完成した文様は邦彦氏そのものだ。無駄がなく洗練され、奥ゆかしく気品溢れる佇まいも果断に富んでいる。邦彦氏の卓越した技は、偉大な人間性ゆえ既得したのだと感慨を受けずにはいられなかった。

文様が奏でるモードの旋律

Melody monyo a la mode: a forgotten fashion

日本の文化や伝統という言葉からどのようなイメージが連想されるであろうか。芸術・学問から衣食住まで、多彩で独自な「和」の風景がさまざまに浮かんでくるだろう。しかし、おそらくその風景の中に「文様」の姿を思い浮かべる人はほとんどいないのではないだろうか。少なくとも江戸時代の終りまで、日本は文様の大国であり、文様を中心としてモードの最先端を走る文化圏であった。不特定多数の人びと(今日で言う「大衆」や「市民」)によって享受される流行の発生は、日本が世界のどの文化圏よりも早かった。それは、文様が流行(=モード)の中心にあって、町人たちが文様で遊ぶ高度な生活様式を確立していたからである。そのことは、きっと忘却されているにちがいない。

What images spring to mind when you think about such icons of Japanese culture or tradition as Japanese art and literature, wooden houses, delicate food, and kimonos? I am sure many colorful and unique scenes of wa (Japanese style) will have arisen. However, very few people will conjure up pictures of monyo (graphic designs and repetitive stenciled patterns) often found on the everyday items of the Edo period. Until at least the end of the Edo period, Japan was a great consumer of monyo, and with monyo as the central motif, the Japanese lived in a fashion culture where clothing design changed very little, but the ever-changing monyo provided an endless source of delight and variety; this constantly changing trend was something unique to Japan and just not seen in other cultures of the time. It has long been forgotten that the appearance of a fashion trend enjoyed by large numbers of town-dwellers was a world first, arising from monyo being positioned at the very heart of fashionable life. Town and city dwellers had already established a sophisticated lifestyle that then allowed them to enjoy playing with monyo as an adornment of everyday clothing.

デザイナー宮崎友禅

Designer Miyazaki Yuzen

その忘れ去られてしまったモードの世界を象徴する人物がいる。今から三百数十年前に活躍した、絵師宮崎友禅である。宮崎友禅と聞くと、友禅染の創始者というイメージを思い浮かべられるかもしれない。しかし、彼は友禅染の技法には関与していない。あくまでも扇絵を描く絵師であり、その評判から小袖模様の作画も手掛けるようになった、いわばデザイナーであった。重要なのは、かれが当時最新であった出版というメディアによって、デザイナーとしてのスター像が築かれていったという点である。友禅の描いた扇絵や小袖模様は、浮世草子などに取り上げられ※1、あるいは当時のファッション誌ともいえる小袖雛形本で喧伝され※2、町人たちの話題となって一世を風靡した。貞享5年(1688)には、彼の名を冠した『友禅ひいなかた』※3という、友禅模様を特集した雛形本まで出版されているのだから、その人気のほどがうかがわれるだろう。

不思議なことに、それだけ有名な絵師であったのに、彼が描いたことが明らかな作品というのは、版本が3点あるのみで※4、そのほかに見出されない。謎の絵師といわれる写楽でさえ、作品は少なからずある。友禅の場合、基準作となる肉筆画が皆無なのだ。しかし、友禅の名は、出版を通じて、あるいは人口に膾炙して、そのイメージは際限なく広がっていった。いつしか友禅の名は、友禅文様を表現する技法の名称となり、江戸時代中期、18世紀の都市景観を様々に彩る要素となっていった。

※1. たとえば井原西鶴は、天和2年(1682)刊『好色一代男』や貞享2年(1685)『椀久物語』などに、都で持て囃される注目のアイテムとして友禅が描いた扇や墨絵の小袖を登場させている。

※2. すでに貞享3年(1686)刊『諸国御ひいなかた』には、「此頃都にはやりしもやうゆふせんふう」といった記述がみられる。

※3. 染工であった友盡斎清親という人物が筆を執った。宮崎友禅に私淑して画風を学んだという。

※4. 元禄5年(1692)刊『余情ひいなかた』、同年刊『和歌物あらかい』、宝永4年(1707)刊『祇園梶の葉』の3点が、奥付によって友禅筆と確認できる。友禅の落款が入った肉筆画や染絵はあるが、筆致や画風などさまざまで、後世に製作された可能性がきわめて高い。

If anyone symbolizes this now overlooked world of monyo a la mode, it is the painter Miyazaki Yuzen who some 300 years ago was a prolific artist and popular star in the public imagination. The name of Miyazaki Yuzen is forever associated with his being the founder of yuzen-zome, a type of dyeing and fabric printing technique, even though no actual evidence exists to confirm his involvement in its discovery. He started his career as an ogi-e artist painting pictures on folding fans, and building on his reputation he moved into creating graphic designs and patterns for the short-sleeved kimono known as kosode; he was actually a highly-talented graphic designer. The important point is that by using the period’s latest publication media, his image as a top designer was being shaped. The ogi-e and kosode designs of Yuzen were taken up by ukiyo zoshi, the popular story books of everyday life in the Edo period.*1 In addition, publishers were promoting designs in the popular kosode design books, the fashion magazines of the day,*2 his designs and elegant models stirred much excitement among town-dwellers and had an extraordinary impact on society. In 1688, clearly indicating his increasing popularity, a design book featuring yuzen designs was published under his own name and entitled Yuzen Hiinakata.*3

Curiously, even though he was such a famous painter, only three printed books can be clearly attributed to him,*4 and no other works have been discovered; even Toshusai Sharaku, the mysterious ukiyo-e artist, left more works to posterity. Although at the time Yuzen’s name was on everyone’s lips and his designs were appearing in endless publications, none of his original paintings, which acted as reference works, have been found. Imperceptibly over the years, the name Yuzen came to refer to a technique used to create yuzen monyo; the technique became an important element in adding color, charm, and elegance to the fashionable urban streets of the middle Edo period in the18th century.

*1. For example, in Koshoku Ichidai Otoko (The Life of an Amorous Man) published in 1682 and Wankyu Monogatari (Tale of Wankyu) in 1685, the author Ihara Saikaku included fans and kosode in brush ink drawings by Yuzen as items attracting considerable attention and praise in the cities.

*2. In Shokoku On-hiinakata published in 1686, the following description was already found: “The latest designs popular in the cities are the yuzen style.”

*3. A dyer named Yujinsai Kiyochika wrote this book. He was a great admirer of Miyazaki Yuzen and followed his style of drawing and painting.

*4. Three pieces, Yosei-hiinakata and Wakamono Arakai published in 1692, and Gion Kajinoha in 1707 can be confirmed by their colophons as having been drawn by Yuzen. There are original paintings and some-e (dyed paining) bearing Yuzen’s signature; however, their brush strokes and styles vary, making it highly likely they were produced in later years.

町人によって自覚されたモードの世界

Townspeople and Monyo a la mode

このようなことは、江戸時代の文化史を繙けば、当然のごとくに記述されている。しかし、18世紀にはまだヨーロッパでも市民レベルのモードというのは成立していない。それに対して、日本ではすでに17世紀の後期には町人たちが「最新」という価値を発見して、流行の自覚的な享受者となっていた。元禄5年(1692)に出版された『女重宝記』という書には、「都の町風も時世に移りかわりて、時々のはやり染も、五年か八年の間にみなすたり」と記されている※5。「五年か八年」というと、ずいぶん悠長な、と思われるかもしれないが、この時代に不特定多数の町人たちが流行を自覚して、能動的に関わっていたということは画期的なことなのだ。スパンの長さは違うにしても、モードに向けられる眼差しは、現代と変わるところはない。このモードの世界は、京都ではいち早く17世紀の半ばに成立している。日本がモードという点で、世界的な先駆けとなった文化圏であったということはまちがいない。

※5.この記述は、巻一の「衣類の沙汰并に染様の事」にみられる。同書は、長友千代治校注『現代教養文庫1507女重宝記・男重宝記』(社会思想社 1993)に翻刻されている。

When the cultural history of the Edo period is studied, it is all too easy to recite the above historical facts without fully appreciating that at this time in the 18th century, even in Europe, this kind of grass root fashion movement had not appeared, whereas in the later 17th century Japan, townspeople had already discovered the value of the “newest,” and they were thoroughly enjoying fashion trends. A book, Onna Chohoki (Women’s Treasury) published in 1692 describes as follows: “Urban manners change with the passage of time, and as for popular pattern dyeing, all go out of style in five or eight years’ time.”*5 Of course, with our seasonal fashions, the modern reader may find “five or eight years” as rather slow, but for the period, it was an epoch-making and completely new way of living for the large numbers of townspeople caught up in the excitement and actively following the latest trends. In essence, even though the timescale is longer, we see an infant consumer society that will grow in to our present era; there is very little difference between now and then. Mid-17th century Kyoto was the birthplace of this movement, and there is no doubt that with its spread to other urban areas, Japan can rightfully claim to be the forerunner of the modern world of fashion.

※5.This description is found in “Matters concerning clothes and dyeing” in Volume 1. The book is reprinted in Gendai Kyoyo Bunko 1507 Onna Chohoki, Nan Chohoki(Women’s Treasury and Men’s Treasury) revised and annotated by Nagatomo Chiyoji (Shakai Shisosha, 1993).

大衆による、大衆のためのアート

Art for the masses by the masses

特記されるべきは、その早熟さだけではない。文様の表現力もまた格別であった。衣服の全面をあたかも画布のように、絵画に比肩される多彩な文様を表現し、たとえ富裕層に限られていたとはいえ、けっして少なくない人々がそのようなデザインの衣服を常用していたのである。このような服飾文化のありようもまた、世界的に見てきわめて異色である。多彩なキモノの柄を見慣れていない海外の人々にとって、その文様は通常の服飾の常識内には収まりきれない存在に映っている。1992年、ロサンゼルスの美術館で江戸時代の小袖の名品を集めた展覧会が開催され、好評を博した。そのタイトルは「When Art Became Fashion Kosode in Edo-Period Japan(芸術がファッションになったとき江戸時代の小袖)」というものだった。これはアメリカの日本文化研究者がつけた名称で、この場合のファッションは衣服の流行に限定してよい。彼らは、キモノの文様を洋服の柄やオーナメントとはまったく異なり、迷うことなくアートだと直感している。西欧的感覚では、結びつきがたいアートとファッション(もちろん大衆による、という意味でモードと言い換えてもいい)が、江戸時代の日本文化においては一体となって存在していた。そこに彼らは魅せられ、とてつもないポテンシャルを感じ取っていたのである。われわれが博物館や美術館で目にすることのできる江戸時代の小袖は、実際に製作され、着用されたもののほんの一部、氷山の一角にも満たない。今では想像もおよばないが、江戸時代には膨大な数の文様が生み出され、当代の人々の視覚を潤していたのだ。どんなに幕府が、贅沢を禁じても、“箪笥の肥やしは人生の肥やし”といわんばかりに、町人たちは文様を生み出し、遊び、その「新しさ」を消費していった。それは壮観で痛快な光景であったにちがいない。

Such an early flowering of popular fashion culture is not the only aspect worthy of mention; the sheer brilliant expressiveness of monyo was also exceptional. The whole area of a kimono became a canvas for the artist, and versatile monyo comparable with pictures were created. Admittedly even though these heart-breakingly beautiful kimono were limited to the very wealthiest of society, it was not uncommon to see people wearing these extraordinary designs on their everyday clothes. When viewing other world cultures of that time, the existence of such a clothing and fashion culture was extremely unusual. For people from overseas who have not grown up with the many and varied patterns commonly found on kimonos, monyo might appear as something that does not easily combine with ordinary clothing and accessories. In 1992, a Los Angeles museum held a much acclaimed exhibition displaying a collection of the finest kosode of the Edo period. US researchers of Japanese culture entitled the exhibition “When Art Became Fashion: Kosode in Edo-Period Japan”, and the term fashion in this context can be limited to clothing fashion. They intuitively knew that the monyo of kimono are totally different from the patterns, designs, and ornamentation found on Western clothes; monyo are without doubt art. In a Western sense, it is difficult to connect art and fashion (of course the word fashion can be replaced with trends, meaning a movement among the masses), but in the Japanese culture of the Edo period art and fashion existed as one entity. The researchers were fascinated by this point, and explored its enormous potential. The remaining kosode of the Edo period that we can see in museums and art galleries are just a tiny sampling of those actually made and worn. It is impossible for us to imagine nowadays the sheer volume of monyo manufactured in the Edo period to enrich the lives and excite the senses of ordinary people. No matter how much the Edo Shogunate attempted to prohibit luxury and extravagance, townspeople continued producing monyo as if to say, “drawer-fodder is life-fodder,” and kept on consuming and playing with fashion and “novelty.” The streets of Edo, Kyoto and other towns must have presented a magnificent and spectacular kaleidoscope of color to delight the eye of the passerby.

近代は、文様をどう捉えたか?

Monyo today

日本の文様の奧深さは、伝統という格式を維持しながら、自在に遊ぶ感覚を合わせ持っている点にある。そこが凄いのだ。たとえば、平安時代の国宝「片輪車蒔絵螺鈿手箱」(東京国立博物館)には流水に牛車の車輪を配した文様が器面いっぱいに表現されている。この文様は、襖絵にも描かれ、調度にも意匠化され、小袖の文様にも表現されていく。流水は叙景的表現などに頓着せずに、うねったり、渦を巻いたり、幾何学図形になったり、植物モチーフと融合したりとその表現は自在である。車輪も単に丸いだけではない。流水のような曲線を描いたり、方形に姿を変えてしまうこともある。どのモチーフも、そのような自由さを内包している。しかも、文様の題材はあらゆるところに見出されていく。日常的な雑物から天象まで、文字通り、森羅万象がモチーフとされ、物語や説話、和歌や漢詩などからも、次々と新しい文様が創案され、発信されていった。どの文様も、時代を越え、ジャンルを超えて飛翔し、自在に装飾空間を満たしている。とくに江戸時代には、壮大な文様の体系を受けとめる装飾の場(江戸時代の小袖はその代表的存在だ)が整えられ、それを鑑賞する深い造詣が市井の日常に根づいていたのだ。

だが、明治時代になると、江戸時代までの文様をめぐる世界は、にわかに儚い存在となってしまう。それは欧化政策による近代化の荒波に揉まれて淘汰された、というだけではない。明治9年(1876)東京医学校の教師として来日したベルツ(1849~1913)の残した『ベルツの日記』には、「現代の日本人は自分自身の過去については、もう何も知りたくはないのです。それどころか、教養ある人たちはそれを恥じてさえいます。」という一文がある※6。教養ある人間ほど、江戸時代までの文化を否定していたという事実は、とてつもなく重い。ベルツだけではない。彼の抱いた懸念や危機感は、当時来日した、いわゆる御雇外国人たちの誰もが抱いたものである。日本人が自らの手で独自の文化を葬り去っていく。その悲劇を眼前にして、誰もが無念さと歯痒さを異口同音に書き残している※7。

では、文様の世界は近代の到来とともに瓦解してしまったのか。いや、けっして消え去ってはいない。“工芸”や“伝統”とよばれる場で、ひそやかに息づいている。その意義や真髄に触れる機会は激減しているが、文様の命脈はしっかりと保たれている。衰微の過程にあるのではなく、啓蟄を待っているのだ。なかでも、“色とかたち”をもっとも自在に表現できる友禅染は、江戸後期に一度流行の表舞台から退いたものの、化学染料の導入や型友禅の発明などで近代に再興した。そのときに、あの宮崎友禅のスター像も復活している。昭和30年以降、キモノの需要後退とともに友禅染の文様も、その居場所を失いつつあることは否定できないが、文様の原点回帰への端緒を開く可能性をもっとも秘めているのは、友禅染といえるかもしれない。

※6.明治9年(1876)10月25日の記事。ベルツ(1849~1913)は同年6月に来日し、明治38年にドイツに帰国した。トク・ベルツ編 菅沼竜太郎訳『ベルツの日記』(岩波文庫1979) 参照。

※7.渡辺京二『逝きし世の面影』(平凡社ライブラリー2005)参照。

The profound depth of Japan’s monyo lies at the boundary where free play and flow in design meets the formal structure of tradition, and gives rise to stunning art as exemplified in the Tokyo National Museum’s national treasure, the renowned Heian period “Tebako (cosmetic box) made of maki-e lacquer and mother-of-pearl inlay.” Oxcart wheels half-submerged in a flowing stream are the inspiration for monyo design covering every surface of the box’s exterior. This monyo also appears painted on fusuma or sliding doors, and crops up as a decoration motif in furniture, and of course, as a motif in kosode. The artist pays no attention to accurately depicting a stream. Rather the stream meanders and playfully swirls, turning into geometric figures, or blending with a plant motif; its expression is unrestricted. The wheels too are equally treated and are not simply round; they describe curved lines like a stream, and some of them evolve into squares. Every single motif is dancing and free.

The subject matter of monyo is drawn from every aspect of life; nothing is too grand or humble, inspiration is as likely to come from banal everyday objects, as it is from heavenly celestial phenomena. Monyo literally consumed the world, and all things in nature were regarded as being suitable as a motif. Inspiration was even found in old folk tales, fables, Chinese poems, and 31-syllable Japanese tanka poems; new monyo were invented and born tumbling one after another into a world eager to welcome them with open arms. All monyo transcend their eras and by taking flight escape the confines of a simple genre and freely inhabit a thousand decorative spaces. Especially, in the Edo period, a fertile ground for decoration ready to accept the magnificent flowering of monyo − a classic example is the kosode of the Edo period − was being cultivated among a sophisticated populace with a deep knowledge and appreciation of design, and the desire to incorporate monyo into every aspect of their daily life.

With the dramatic birth of the Meiji period, the elegant never-ending world surrounding monyo was seen to be transient and suddenly collapsed. The reasons were not simply limited to the violent upheavals marking the end of an insular era or the painful adaptation to modernization with the increasing policy of Europeanization. In the book Awakening Japan: The Diary of a German Doctor, written by Erwin Bälz (1849 ‒ 1913), who was invited to Japan in 1876 as a lecturer at the Tokyo Medical School, the author observed: “Modern Japanese people no longer want to know anything about their own past. On the contrary, well-educated people are even ashamed of their past.”*6 The fact that the better-educated a person was, the more they turned their back on centuries of Japanese traditions and culture was extremely serious for the health of society. Bälz was not alone in his observations, every foreign specialist in the employ of the new Government also reported their concerns and this sense of impending crisis. Before their eyes, Japanese people were busily abandoning and burying their unique culture with their own hands; these foreigners in their diaries and letters unanimously noted their regret at this tragic denial of tradition.*7

Against such a tumultuous background, the reader may wonder “Did the world of monyo shatter into a thousand pieces with the abrupt arrival of modern times?” Fortunately, the answer is no; it did not collapse and it did not fade away, rather it flew just a short distance to the fields of “crafts” and “tradition,” where it has been quietly living for over a century. Obviously the opportunities to feel its significance and essence have sharply declined, but the thread of life of monyo has been tightly spun, and it is certainly not decaying, more hibernating like a butterfly waiting for the spring to come.

Yuzen printing, even in the later Edo period, had been losing popularity and was no longer at very center stage of fashion, but today this technique allowing the freest expression of “color and shape” has revived thanks to the introduction of chemical dyes and invention of a style of kata-yuzen (stencil-dyed). With this revival, the star image of Miyazaki Yuzen is once more in the ascendant. It is undeniable that after 1955, along with a fall in the demand for kimono, monyo for yuzen printing is losing ground, but it might be the destiny of yuzen printing to help revive and take the first steps of the return to the origin of monyo.

※6.An article on October 25, 1876. Erwin Bälz (1849 ‒ 1913) came to Japan in June 1876, and returned to Germany in 1905. Refer to Awakening Japan: The Diary of a German Doctor edited by Toku Bälz and translated into Japanese by Suganuma Ryutaro (Iwanami Bunko, 1979).

※7.Refer to Yukishi Yo no Omokage (Vestiges of Past Worlds) by Watanabe Kyoji (Heibonsha Library, 2005).

文様は再び飛翔する

Monyo will fly again

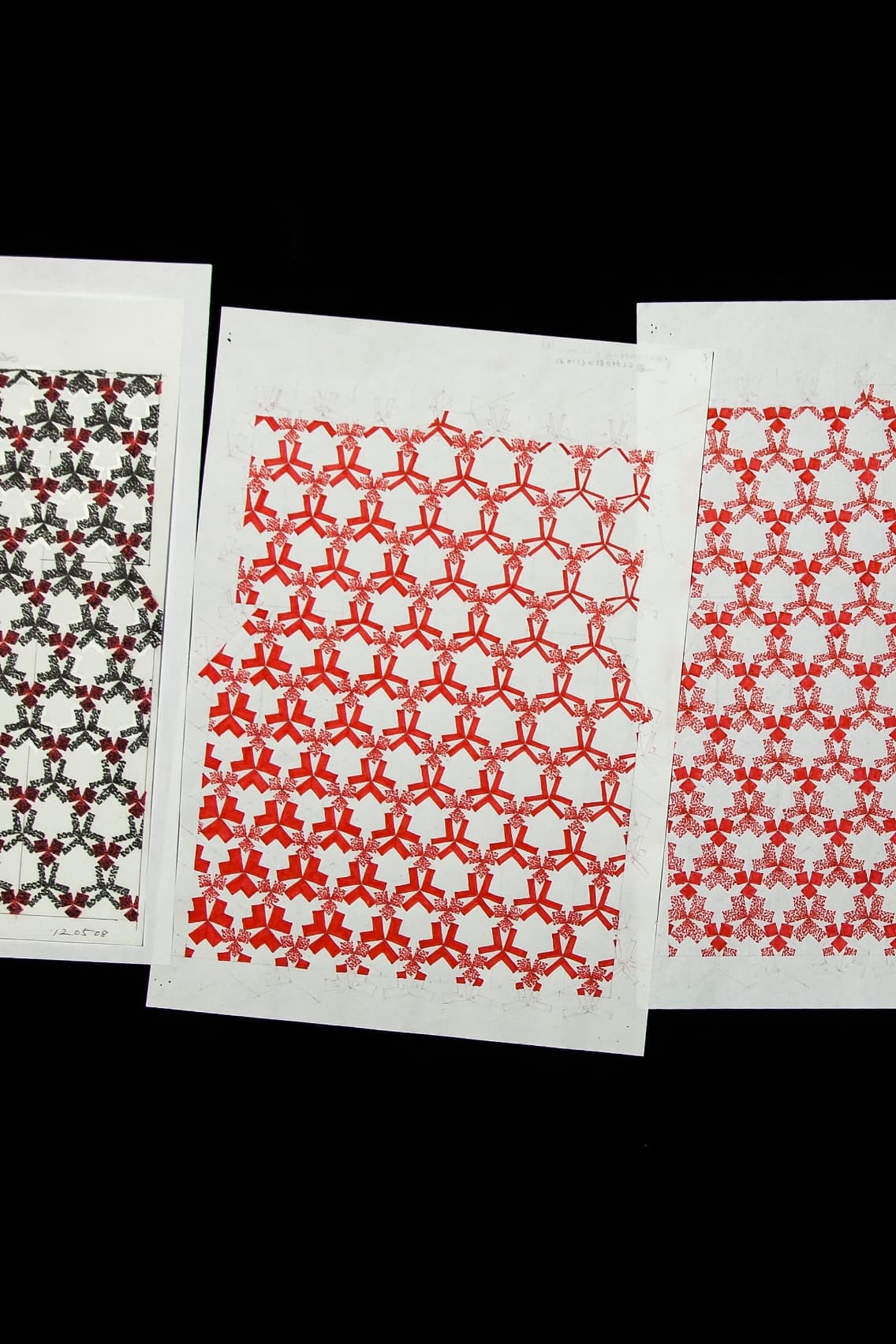

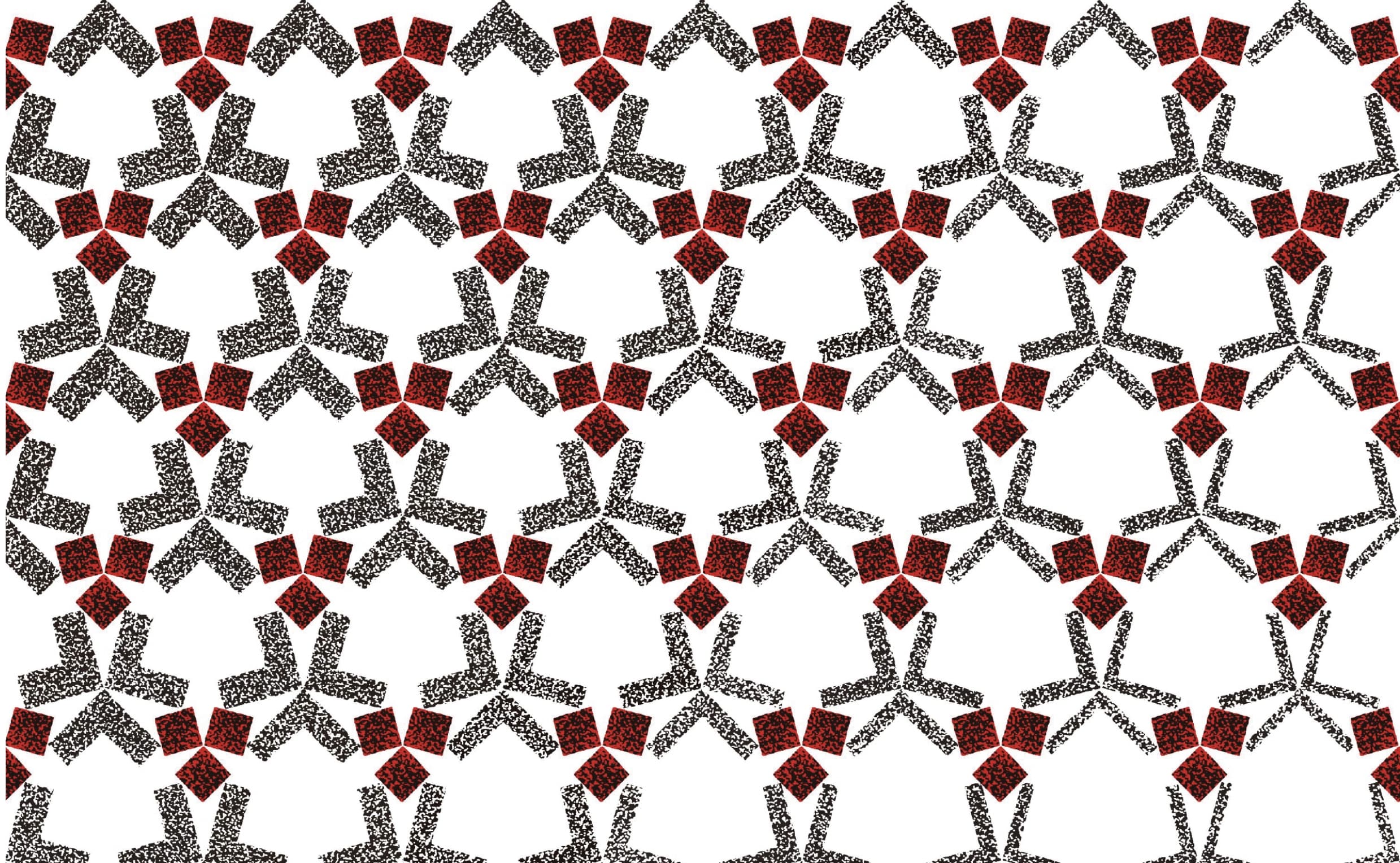

今、森口邦彦氏の作品を前にして、『友禅ひいなかた』の一文を思う。宮崎友禅に私淑したこの雛形本の筆者友尽斎清親は、匂い袋、色紙、短冊、畳紙、手箱、櫛、杯などにも「絵かゝすといふ事なし」とし、友禅の文様が小袖以外のさまざまなものに応用できる旨を強調している。キモノの文様、とりわけ友禅の系統には、文様を飛翔させる底力がある。森口氏のこのデザインもそうである。一瞬、幾何学的な連続図形のように見えながら、実は手描き友禅でしか表現できない、絶妙な旋律的デザインとなっている。しかも、この文様は着用するとがらりと表情を変える。作者は、そういう二面性を遊び心として、デザインのなかに仕込んでいる。この遊び心は、文様の位置を少しでもずらしたら、破綻してしまう。そういう危うさと完璧性の上に成り立っている。それでいて、キモノの枠のなかだけに留まらず、ジャンルの垣根を軽々と飛び越え、どのような対象においてもまた絶妙の旋律を奏でる魅力と存在感を合わせ持っている。まさに「絵かゝすといふ事なし」という江戸時代の友禅文様の現代版といえる。

今、ひとつのキモノのデザインが、一条の光となって文様の世界を照らし出そうとしている。装いから発信されて、生活のあらゆる場に飛翔していく文様の姿。その展開を実感できれば、それは文様という、世界に誇るべき知的財産の記憶を取り戻す絶好の機会となるはずである。

Confronting this work by Mr. Moriguchi Kunihiko, the words of Yujinsai Kiyochika, a passionate admirer of Miyazaki Yuzen, immediately come to mind. In his book Yuzen Hiinakata he so eloquently stated, “With Yuzen’s monyo, all is perfect.” He meant that when monyo appear upon such everyday items as scent bags, colored paper, strips of paper, folding paper-cases, cosmetic boxes, combs, and sake cups, they are a perfect fit, and thus emphasized the point that Yuzen’s monyo are not just at home on kosode, but are perfect for everyday adornment of innumerable articles. As seen in a thousand kosode, monyo for kimono, particularly with the yuzen style imparts a latent energy that brings the monyo to vibrant life. The design by Mr. Moriguchi follows in this great tradition; at first glance the eye sees a continuation of geometric figures, but with contemplation an exquisite melodious design is revealed, which can only be expressed by employing the hand-drawn yuzen technique. Moreover, when draped and flowing with movement, this monyo radically changes its appearance. The artist cleverly embedded these two faces to convey a playful mood within the design. Even the faintest breeze from a butterfly’s wing quivering against the monyo would collapse the work; underlying the design is a perfectly balanced and delicate web of exact dimensions. Even so, it does not just sit tame and quiet within the boundary of the kimono, but like a butterfly flutters here and there crossing the genre, and displaying both its beauty and presence, happily plays among many other objects. It is truly a yuzen monyo for our times, a child of the original yuzen monyo of the Edo period, a fitting testament to Kiyochika’s “With monyo, all is perfect.”

Now, this one design for kimono is set to become an icon, a beam of light illuminating anew the world of monyo. This deceptively simple monyo born for personal adornment is set to fly free among the ten thousand things of daily life. Enjoy this unfolding of the monyo butterfly, a golden opportunity for us all to revive the memory of a long lost era and an art form that is the envy of the world.

※森口邦彦氏の「邦」の異体字は、ブラウザで正しい表記ができませんこと、ご了承ください。

丸山 伸彦

Maruyama Nobuhiko

1983年 東京大学文学部美術史学科卒業。

1985年 東京大学大学院人文科学研究科修士課程修了(専攻:日本美術史)。

1985年 国立歴史民俗博物館助手。

1997年 国立歴史民俗博物館情報資料研究部助教授。

2000年 金沢美術工芸大学助教授。

2003年 武蔵大学人文学部日本・東アジア文化学科教授(現職)。

1983: Graduated from Department of Art History, Faculty of Letters, The University of Tokyo

1985: Completed Master’s Program, Graduate School of Humanities, The University of Tokyo (Majored in Japanese art history)

1985: Assistant, National Museum of Japanese History

1997: Assistant Professor, Information Reference Research Department, National Museum of Japanese History

2000: Assistant Professor, Kanazawa College of Art

2003: Professor, Department of Japanese and East-Asia Studies, Faculty of Humanities, Musashi University (present post)