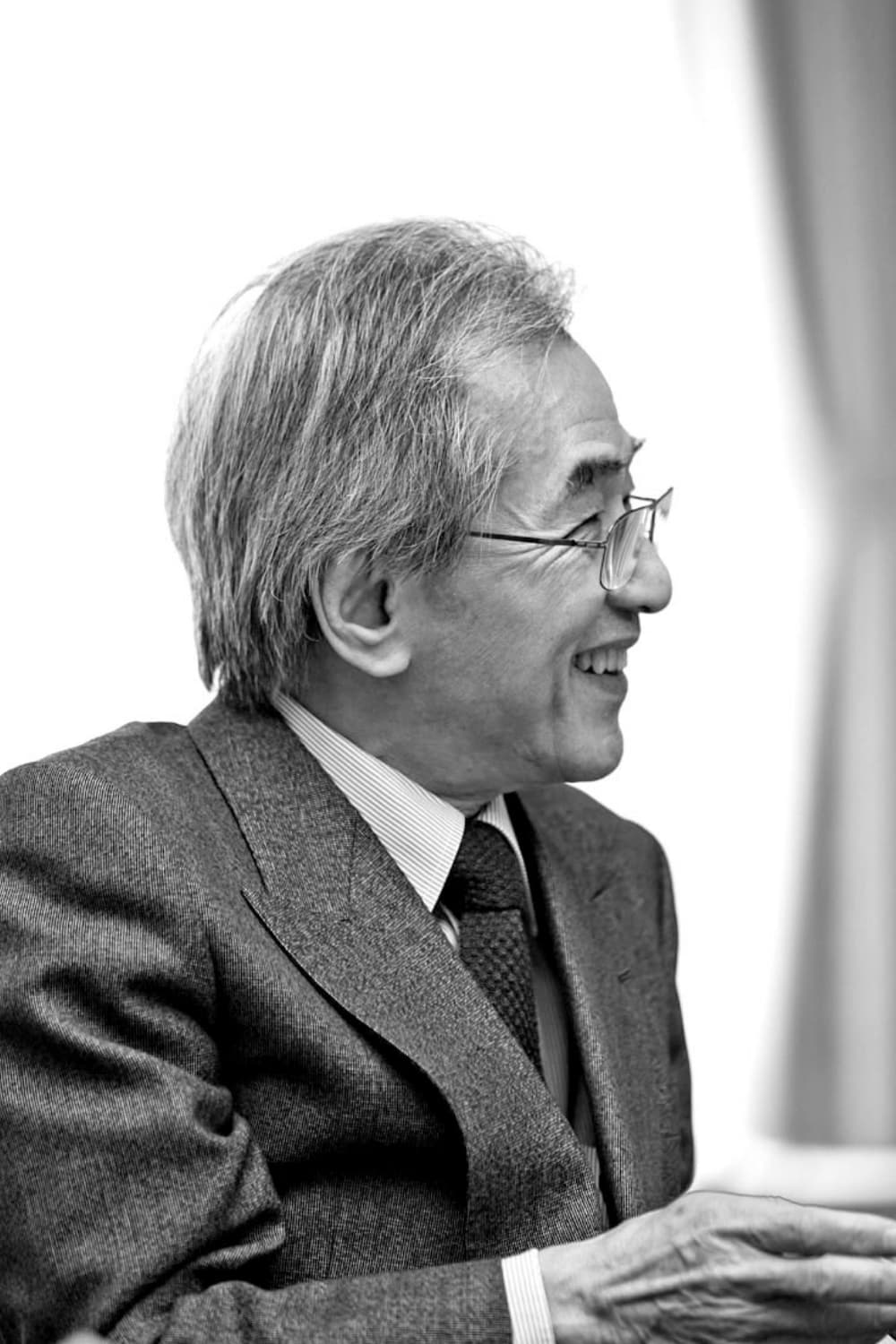

旧友同士の対談

森口邦彦×

フィリップ・ワイズベッカー

Moriguchi Kunihiko x Philippe Weisbecker | A talk between old friends

森口邦彦 ×

フィリップ・ワイズベッカー

旧友同士の対談

Moriguchi Kunihiro x Philippe Weisebecker - A talk between old friends

今日は対談をお受けいただきありがとうございます。最初にお二人の最初の出会いや、その後どのような経緯で今に至るのかをお聞かせください。

森口 邦彦 (以下 森口):1963年、私はフランス政府給費留学生の奨学金を得て、パリ国立高等装飾美術学校に留学することになり、一方、フィリップは1962年にすでに入学していました。

フィリップ・ワイズベッカー (以下 ワイズベッカー):その通りです。

森口:彼は通常の学生として一年生から入学していたのですが、私は京都市立美大を卒業していたので、一年生を飛ばして1963年、直接、二年生に編入したのです。そのおかげで私たちは同学年の同じアトリエで出会うことになりました。一学年から三学年までは混成で四つのアトリエに分かれています。もし二人が別々のアトリエに所属していたら出会うこともなかったかも知れないのですが、たまたま二人ともシェドー教授のアトリエだったのです。こうして同じアトリエで二年間、一緒に学びました。四年生になると専門を選ばなくてはなりません。

ワイズベッカー:それがグラフィック・アートだった。

森口:そう、二人ともグラフィック・アートを専攻したのです。そういうわけで私たちは三年間学業を共にしました。その後、私は日本に帰国し、彼はニューヨークへ向かいました。彼はニューヨークでイラストレーターとして名声を得ることになります。キャリアが花開いたわけです。そのニューヨーク生活も終わりに近づいた頃、彼はフランス政府の給費を得て、京都に有るフランス人のための滞在型文化施設、ヴィラ九条山に4ヶ月間、滞在することになったのです。

森口:2002年のことです。その当時の私は、彼がどういう人生を送っているのか全く知りませんでした。何となく風の便りに噂は耳にしていましたがね。何となくね。

ワイズベッカー:何となくね。

森口:卒業後は再会の機会もなかったわけです。でも、京都にやって来た彼はありがたいことに私を探してくれたんです。でも…。

ワイズベッカーさんは、京都に森口さんがいると確信していらっしゃったのですか。

ワイズベッカー: まさにそこが面白いところです。京都に来た時も、クニのことは強烈に覚えていました。学生時代に少しフラッシュバックすると、初めてクニに出会った時から、彼の存在そのものに魅了されていたんです。何しろ当時フランスで日本人を見かけることなどめったになく、それだけで非常にエキゾチックな存在でしたからね。でも、それだけじゃありません。彼が手がける作品の完璧さにも圧倒されていたのです。そうそう、私が驚嘆したことがあります。当時、パリ国際大学都市に住んでいた彼をある朝、たずねました。彼はほんとに小さな部屋に住んでいました。でも彼はその狭い部屋で壮大な建築プロジェクトを構想していたんです。なんてすごいやつなんだ、と思いましたね。当時、シェドー教授は、彼の才能を正当に評価していなかったように思います。主観的でした。そして私はクニの言葉に圧倒されました。「毎朝、僕が起きてすぐにすることはね、蓮華のポーズ(=あぐら座り)を組み、長い軸の筆で、まっすぐな線を何時間も描き続けるんだ」。私は、彼は神だ、と思っていましたね。

卒業後、お互い音信不通の年月が流れました。私はニューヨーク暮らしをしていましたからね。ヴィラ九条山に滞在が決まって京都にやって来た時にも、きっとクニは世界のどこか別の国で建築家として大成しているに違いないと確信していました。でも、クニのお父さんがキモノの人間国宝で、京都にお住まいであるということは知っていました。なので京都にまだクニの実家があるとは思っていました。そこで関西日仏学館(現・アンスティチュ・フランセ関西)で、以前、私のために仕事をしてくれたことのあるグラフィックデザイナーに訊ねてみたのです。「クニヒコ・モリグチという人をご存じですか?」。すると彼は「森口さ〜〜〜ん!!」(=畏れ多い感じで)と声をふるわせたんです(笑)。なので、森口という人が有名であることはわかりました。きっと彼のことだ、と思ったのですが、モリグチさんがクニのことなのか、お父さんのことを言っているのか定かではなかったのです。

ワイズベッカー: 当時、ヴィラ九条山にはフランス人写真家が滞在していまして、彼の展覧会のオープニングパーティーに、どうやらクニが来るらしいと知りました。どうやって知ったかは失念しましたが。クニのほうでは、私がそのパーティーに来ることは知りませんでした。

森口: そう。

ワイズベッカー:私はパーティー会場に着きました。そしてクニの姿を見つけたのです。クニも私に気づきました。二人はすぐに駆け寄って抱き合ったんです。

すぐにお互いにおわかりになったんですか。

森口:そう38年たっていてもね。

ワイズベッカー:二人が互いに気づいたのは同時だったね。

森口:そう、同時。つまり、二人とも変わってなかったんだ。

ワイズベッカー:変わってなかったんですよ。感動的な再会でした。クニが京都にいるはずがないと思っていましたからね。学生時代のクニの技量からすれば、きっと建築家になっていると想像していたんです。おかしいですよね。

本当にそうですね。その後は、コンスタントにお会いになっているんですか。

森口/ワイズベッカー:そりゃあ、もちろんですよ。

Thank you very much for coming along today. First of all, please tell me how you met, and how your friendship developed.

Moriguchi Kunihiko (hereinafter, Moriguchi): In 1963, I went to France to study at the National School of Decorative Arts in Paris (École nationale supérieure des Arts Décoratifs) on a French government scholarship, and that’s where I met Philippe. He had enrolled in the school the previous year, 1962.

Philippe Weisbecker (hereinafter, Weisbecker): Yes, that’s right.

Moriguchi: As a regular student, Philippe had started from the first-year course, but as I had graduated from Kyoto City University of Arts, I skipped the first-year classes, and in 1963, I enrolled directly into the second-year course. Thanks to these events, we were in the same school year and met in the same atelier. There were four mixed ateliers, consisting of the first to third-year students. If we had belonged to different ateliers, we might never have met, but just by chance both of us were in Professor Shedo’s atelier. So we ended up studying together in the same atelier for two years, and for the fourth year, we had to select a specialty.

Weisbecker: We both chose graphic art.

Moriguchi: Yes, both of us majored in graphic art, and so we were studying together for three years in total. After graduation, I went back to Japan, and Philippe left for New York, where he made his name as an illustrator. His career blossomed. After many years he decided to leave New York and he applied for a French government scholarship. This meant he was able to stay for four months in Villa Kujoyama, a residential cultural facility for the French, located in Kyoto.

Moriguchi: That was in 2002, and around then I had no idea what he was doing, but I did hear a few rumors on the grapevine, the odd vague whisper.

Weisbecker: Vaguely.

Moriguchi: After our graduation we did not really have any opportunity to meet again, but fortunately when he came to Kyoto, he tried to look me up. But…

Mr. Weisbecker, were you convinced that Mr. Moriguchi was in Kyoto?

Weisbecker: That is a good point. When I came to Kyoto, I still had strong memories of Kuni. If I flash-back to our school days, from the first time I met Kuni, I was fascinated by his physical presence. As you know in those days we hardly saw Japanese people in France; that alone made them seem pretty exotic. But that’s not all. I was overwhelmed by the perfection of his work. Oh, yes I can clearly remember being struck with admiration. He was staying in the International University Campus in Paris, and when I visited him one morning, I was surprised to find just how small his room was, but despite this, seeming lack of space, in his mind he was always shaping really massive and magnificent architectural projects. I thought what an amazing guy. In my opinion, at that time, Professor Shedo did not properly appreciate his talent; his view was a bit subjective. But in my case, I was blown away by Kuni’s description of his daily morning practice: “Every morning, immediately upon arising, I sit in full lotus (cross-legged), and for some hours I practice drawing straight lines with a long stemmed brush.” I thought he was a god.

After graduating, years passed with no contact. As you know I was living in New York. After my stay in Villa Kujoyama was confirmed and when I came to Kyoto, I was convinced that Kuni must have become a great architect somewhere outside Japan. But I knew Kuni’s father was a living national treasure, a kimono artist, and his family home was in Kyoto. Therefore, I figured there was a good chance that Kuni’s parents’ home would still be in Kyoto. So I made inquiries at what is now the Institute France Kansai, and I asked a graphic designer who had worked for me before: “Do you know about Kunihiko Moriguchi? Then, he exclaimed in a loud voice full of awe “Moriguchi-san!! Of course.” (Laughter) I sort of got the idea this Moriguchi character was famous. I thought he was talking about Kuni, but I still wasn’t absolutely sure, it could have been Kuni’s dad, after all.

Weisbecker: At that time, a French photographer was staying in the Villa Kujoyama, and I got to know that Kuni was likely to come to the opening party of the photographer’s exhibition. I have forgotten how I came to know this, and Kuni had no idea that I was invited to that party.

Moriguchi: No I didn’t.

Weisbecker: I arrived at the party, and then I saw the figure of Kuni. Kuni also noticed me.

Instantly both of us rushed up to each other and hugged.

Did you recognize each other straightaway?

Moriguchi: Yes, even though 38 years had passed.

Weisbecker: We noticed each other at the exact same moment.

Moriguchi: Yes, at the same time. In other words, both of us hadn’t changed.

Weisbecker: No, we hadn’t. It was really emotional, especially as I had believed that Kuni was definitely not in Kyoto. Thinking back on Kuni’s ability and skill in our school days, I imagined that he would have certainly been an architect. That’s funny, isn’t it?

Yes, it is. After your reunion, have you seen a lot of each other?

Moriguchi/Weisbecker: Yes, of course.

日常に存在する真実の美を選びとり、

現代的な手法で後世に残す。

2人の天才のフィロソフィー。

Find and take the beauty of truth hiding in daily life,

and using contemporary techniques record it

for future generations.The philosophy of two geniuses.

森口:彼の仕事は本当に素晴らしいと思っています。非常にシンプルでありながら、非常に奥深いものがあるんです。彼の作品はどれも大好きですね。彼は京都に滞在していた4ヶ月間、(訳注:ワイズベッカーのイラスト本を見せながら)千本通りにあるこういう金づちなど金属製の工具を作る職人の店に通っていたんですよ。この店のご主人は、私の父の右腕だった男性の隣人だったんです。覚えてるかい?(ワイズベッカー:いや、知らなかった)この店のご主人は、私の父の右腕の人の自宅の隣に店を構えていたんだよ。(ワイズベッカー:知らなかったよ)だから昔から良く知ってた人なんだ。私のハサミも彼が作って手入れし続けてくれたんだよ。

ワイズベッカー:面白いよね。そして私はそのご主人のもとに通うようになったのですが、最初からすんなりというわけではありませんでした。私には何かお願いする勇気もなく、黙って見ているだけでした。でもご主人は少しずつ私の存在を受け入れてくれて、道具のデッサンを描いたり、手にとってながめたりするのを許してくれるようになったんです。そんなふうにして…。

森口:そう、職人というのは、仕事に集中しているときに外国人が来ても、正直、邪魔になるわけです。(ワイズベッカー:なるほどね)どうしたって迷惑になるわけですね。だから最初はきっとご主人もあまり気が乗らなかったと思いますよ、でもフィリップは心を通じあわせることに成功した…。とにかく、この道具を描いたこと、これは本当に正しい選択だと思う。ここには何か本物がある。そこにこそフィリップの素晴らしさがあります。日本の日常に存在するオブジェ(モノ)に対する彼の視線が素晴らしい。彼が選びとるものには本当に真実があるんです。そこが好きなんです。ん、なんだか、君が主役の対談になってきたな!

ワイズベッカー:(爆笑)

森口:人はそんなふうに興味をもち始めるのです…。私の仕事は日本では伝統芸術と考えられているものです。ただ彼のようなフランス人にとっては、ひょっとすると職人仕事(アルティザナ)であって、アート(芸術)ではないのかも知れません。職人仕事以上のものではないと。でも、私の仕事(作品)について話しているうちに、日本の職人仕事の裏には哲学(フィロソフィー)があることに気づき始めるのです。彼にとっては大きな発見だったと思います。

ワイズベッカー:私とクニの考え方が共通する点は、本質的なものの美を現代的な方法で後世に残していきたいと思っている点です。クニの場合、その対象は着物であり、私の場合は、シンプルなオブジェ(モノ)、流行や人為的な変化の影響を受けていないオブジェ(モノ)です。クニはそういう姿勢で多くの作品を生み出してきたんです。

森口:(笑)

ワイズベッカー:私もそうだけどね。

Moriguchi: I consider his work is truly wonderful, marvelous. Very simple, but very deep. I like any of his pieces. Have a look at some of his drawings in this illustration book. Over the four months of his stay in Kyoto, he took to visiting the shop of an artisan on Senbon-dori street, who made metal tools such as hammers like this one in this book. Actually this toolmaker and owner of the shop was a neighbor of the man who was my father’s right-hand man. Do you remember the connection?

Weisbecker: No, I didn’t know about that.

Moriguchi: The toolmaker’s shop was right next door to the home of my father’s right-hand man.

Weisbecker: Gosh, I really didn’t know that.

Moriguchi: So I knew the toolmaker pretty well for a long time. He made my scissors and keeps them in good shape.

Weisbecker: Isn’t that interesting? So, I began visiting the toolmaker regularly, but it wasn’t like I was readily accepted from the beginning. I didn’t have the courage to ask much, and mainly just kept watching, saying very little at all. Slowly the toolmaker accepted my presence, and then, he allowed me to draw sketches of the tools and hold and closely look at them. In that way…

Moriguchi: Yes, for craftsmen, when they are concentrating on their work and a stranger comes to see them, frankly speaking, it’s just bothersome.

Weisbecker: I see.

Moriguchi: Like it or not, they find it annoying. So I am sure at first he didn’t warm up very much, but Philippe was successful with heart-to-heart communication… Anyhow he drew this tool you can see here in the book; I think this was really a great choice. I can really see something authentic. It’s exactly here that we can see the brilliance of Philippe. His eye for objet (object or mono in Japanese) present in Japanese daily life is wonderful. What he finds and takes is the real truth. I like this point. Mmm, somehow you’re becoming the main focus in this talk!

Weisbecker: (Burst of laughter)

Moriguchi: People start to get interested in that way… In Japan my work is regarded as traditional art. But for French people like Philippe, it might be thought of as artisan’s work (artisanal), and might not be art. They think it is nothing more than artisan’s work. But, while we were discussing my work (pieces), we noticed that underlying the work of Japanese artisans there is a philosophy. I think it was a great discovery for him.

Weisbecker: The common point in our thinking is that both of us want to leave the essence of beauty to future generations by using contemporary methods. In the case of Kuni his subjects are kimono, and in my case they are simple objet or mono; in particular they are objet or mono, which are not or have not been affected by fashion or artificial changes. Kuni has continued creating many works through this approach.

Moriguchi: (Laughing)

Weisbecker: So have I.

バッグの構造と着物の柄と。

三越の歴史と友禅の歴史と。

2つが交わるとき、伝統は進化する。

Structure of the bag and the kimono patterns.

The history of Mitsukoshi and yuzen.

When two aspects intersect, tradition evolves.

森口先生、今回、三越と一緒にお仕事をされることになった経緯をお聞かせ下さいますか。

森口:まず2013年6月に三越のご担当者が京都まで私を訪ねて来て下さり、三越の新しいショッピングバッグの企画についてお話しされました。私には想像を絶するようなご提案でした。ですが、ちょうど、第60回日本伝統工芸展に出品する作品を完成したところでした。それで、私が提案させていただいたのは…。

今、日本の伝統工芸をめぐる状況は、これまで通りのあり方を維持しようと思うとなかなか厳しいものがあります。この状況を打破したいという思いがありました。そこで私は次のように提案させていただきました。「三越さんにはこの着物をコレクションしていただきます。そして、ちょうど美術館がコレクションからミュージアム・グッズをつくるように、私が力になれる部分があるとすれば、その着物の柄をショッピングバッグに応用することです。私はもともとグラフィック・デザインを学んだ人間ですから、ただ単に着物柄をそのまま紙にプリントするのではなく、バッグの立体的な構造を考慮に入れた上で、バッグの構造が着物柄と戯れるようなそんなバッグをめざしたいと思うのです」。

そういうお話をしてから3ヶ月、いやすでに4ヶ月がたちました。ようやく最終的な形が見えつつあります。創業340年以上の歴史をもつ三越にとっては、今回の新しいショッピングバッグは、新たな道で再出発するという意味あいがあると思います。私は常に、伝統の進化(変革)をあらわしたいと思っています。友禅染めの伝統を振り返れば、友禅の技法も大体、三越と同時期に誕生しています。三越と伊勢丹は統合したわけですが、私はこの統合が幸せな結婚であって欲しいと思っています。そのためには、両社がそれぞれの個性(アイデンティティ)を見出し続けることが大切です。両社の文化は全く違うものですから、ないまぜになってしまってはいけないのです。違いを明確にさせる意味でも、三越は「染め」、伊勢丹は「織り」というふうに、2つの個性は補完的存在であるべきなのです。

Mr. Moriguchi, could you tell me about how you came to be involved in this collaboration with Mitsukoshi.

Moriguchi: First of all, in June 2013, a representative of Mitsukoshi visited me in Kyoto, and talked about ideas for Mitsukoshi’s new shopping bag. For me, this was a very surprising proposal. It was around the time that I had just completed my work to be shown in the 60th Japan Traditional Art Crafts Exhibition. Then, what I suggested was…

Today, the circumstances surrounding Japanese traditional crafts are quite tough when considering we want to maintain the way things were done in the past. I wanted to break free, so I made the following proposal: “Mitsukoshi will add this kimono to its collection, and just like a museum producing museum goods by incorporating patterns and the like taken from its collections, the kimono pattern will be used on the carrier shopping bag; if there is a part where I can be of help, it would be application of the pattern onto the bag. I am an artist who originally studied graphic design; so I want to create the kind of bag, where the three-dimensional structure of the bag will play and interact with the kimono pattern. It’s not just simply printing the kimono pattern on the bag any old how; everything’s carefully thought out.”

After that first conversation three months, no four month have passed. Finally we are nearing completion of the project. I think, for Mitsukoshi, with a history of more than 340 years since its foundation, this new shopping bag implies a fresh start on a new path. I always want to express evolution or the re-volution of tradition. When we look back at the tradition of yuzen printing, the yuzen technique was also born at roughly the same period as Mitsukoshi. Mitsukoshi and Isetan have merged, and I wish this joining will be a happy marriage. To achieve this hope, it is important for both companies to continue discovering their own and the other’s identity. The cultures of these two companies are totally different; therefore, they must not be blended. In a sense that clarifies the difference, the two distinct identities should complement each other, just like Mitsukoshi being known for “dyeing,” and Isetan for “weaving.”

葛飾北斎は

70才を超えて傑作を作った。

僕らにはまだ時間があるんだ。

Katsushika Hokusai produced masterpieces.

Whe he was over 70,We still have time.

森口:今回、ショッピングバッグのデザインに関しては、デザイナーの力を借りて、コンピューターを使い、新たな解釈をしてみました。今回はこういうアプローチが必要だったと思います。コンピューターのおかげで、デザインのアレンジも容易に実現できました。手仕事でやろうとしても無理だったと思います。とはいえ、デザインをどういうふうに展開するかは私自身のアイデアでした。今回は、有意義な試みでしたね。

森口先生は今回、多くの人々を対象に制作する機会を得て、念願が叶ったような、さぞかしホッとされたのではないでしょうか。

森口:そうです。今後も継続されることを願ってます。伝統工芸品、伝統的な生活、伝統文化、そうしたものは今、危機の一途をたどっています。例えば、畳の消滅です。ですから、私たちが伝統を存続させていくための方法は、より…。

ワイズベッカー:そう、あるがままを存続させるのではなく、進化させながらということです。

森口:そう願いますね…。今回の企画を活路に、ふだんの生活の中で伝統文化の再生が始まるのだと言っていただけるのはとてもありがたいことです。そうなることを願ってます。今、私はそうした境目に立ち会っていると思うのです。人生の最後に、次世代にメッセージを送るような気持ちです。

ワイズベッカー:いやいや、君の人生はまだ終わっちゃいないよ。北斎の本を買って読んだところ、彼の最高傑作は70才から80才の間に制作されたらしい。だから僕らにはまだ時間があるんだ。

森口:そうかな。僕も北斎が80才の時に出した本を持っているんだけど、そこには「私の死後何百年たっても私のような絵師は出てこないだろう。だから私は後世の人々のために今、目に見えるもの全てを描きのこす」とある。彼は後世を念頭に入れて作品を残すんだ。正真正銘の巨匠だね。

ワイズベッカー:(今回の企画で)君の前に今、新たな世界が開けたんだ。伝統を維持するだけじゃなくて、開かれているんだよ。

森口:そうだね。

伝統の保護というのは、維持しながらも、新たな可能性の広がりを意味する、それは…。

森口:三越にとっても(今回の企画の)良い結果がでることを私は願っています。三越もまた340年という、やや荷の重過ぎる歴史を背負って、今、新たな道を模索していると思うのです。新たな道、活路は必ずあると確信しています。それは、文化を売る商人としての三越の社会に対する使命のようなものかも知れません。非常に重要なことですよ!

森口先生、今回のデザインの構想について少しお話しいただけますか。

森口:いや、フィリップと同じでね、非常に説明するのは難しいんです(笑)。ただ、こういうショッピングバッグは世界どこを探しても例を見ないと思いますよ。六角形が位相的に展開するデザインで、今回は3つの正方形との組み合わせです。(司会:折り目も考慮されているそうですね)そうです、つまり、ほらこの六角形は、完全な正六角形ではなく、少しタテが長いんです。この幅のために、私は六角形の比率を変えなくてはならなかったわけです。こういう変更が容易にできたのもコンピューターのおかげです。

ですが、このように形を変えるというアイデアは私のオリジナルです。突き詰めていえば、私はこのモチーフをデザインしているわけではないんです。この余白の部分をデザインしているのです。余白のほうが重要なのです。パリの装飾美術学校でも教わったことで、余白をデザインするということです。

ワイズベッカー:それは意識していませんでした。確かに、今、クラスカギャラリーで展示されている私の作品も、建造物のシリーズですがまさに同じことです。建造物は線で描かれている。それぞれの建物は小さいものですが、全体は大きな作品です。ここで大事なのは建物ではなく、余白の部分です。

森口:本当に意味を持つのは余白ということだね。建物と建物のあいだの余白にリアリティがある。それは建物でもなく…。

ワイズベッカー:その通りです。建物はひとつの口実なのです。

森口:ちょっと哲学的な話だね。

ワイズベッカー:君の口からそういう話が出るとは、不思議だな。

森口:意味があるのは余白ということだね。

Moriguchi: As for the design of the shopping bag, I asked a designer to help, and used a computer, and tried new interpretations. I thought such an approach was necessary for this project. Thanks to the computer, I was able to easily arrange the design. If I tried to do this all by hand, it would not work out. And yet, it was my own idea how to develop the design. The project was a worthwhile effort.

Mr. Moriguchi, through the project you had an opportunity to produce a work available to many people; this was like your dream has come true, and I dare say you feel reassured now.

Moriguchi: Yes, I do. I hope that it will be continued. Traditional craft products, traditional life, and traditional culture; these kinds of things are now undergoing a crisis. For example, the extinction of tatami mats. On those grounds, a way for us to ensure tradition will continue is, more…

Weisbecker: Yes, it is not to continue them as they were or are; it is to continue them while letting them evolve.

Moriguchi: I wish so… I very much appreciate your saying that the project will be a way out of a difficulty in traditional culture, and that its resurrection will start in our daily life. I wish it will happen. I think at present I am witnessing such a boundary. I feel like I am sending a message to the next generation at the last stage in my life.

Weisbecker: No, no, your life hasn’t finished yet. I have bought and read a book by Hokusai and I learnt his masterpieces were produced in his 70s and 80s. So, you see we still have time.

Moriguchi: Is that so? I too have a book written by Hokusai at the age of 80, and he mentions: “After my death, even if hundreds of years will have passed, a painter like me will not appear. Therefore, for the people of future generations, I will draw and leave all visible things now.” He left his works having the future generations in mind. He was an authentic great master.

Weisbecker: (With this project) Now, in front of you, a new world has unfolded. It is not just maintaining tradition; such a new world is now opening.

Moriguchi: Yes it is.

Weisbecker: To preserve tradition means not only maintaining the old ways, but also broadening ourselves to new possibilities. It is…

Moriguchi: I wish that Mitsukoshi as well will benefit from this project. I am sure for Mitsukoshi too, carrying 340 years of history on its back, it’s a bit of a burden, and they’re now searching for a new path. I strongly believe there is definitely a new path and a means of survival. It might be the social mission of Mitsukoshi as a merchant selling culture. It is a very important task!

Mr. Moriguchi, could you tell me a little about the concept for the design of the bag?

Moriguchi: Well, it’s the same as Philippe, it is very difficult to explain (laughter). The only thing is, I am sure for this kind of shopping bag no similar example will be found anywhere in the world. It is a design where hexagons spread topologically, and this time they are combined with sets of three squares.

I’ve heard you also took the creases into account.

Moriguchi: That’s right, to be more precise, see, this hexagon is not a perfect hexagon, the height is slightly longer. Because of this width, I had to change the ratio of the hexagon. It was the computer that enabled such a change to be easily made.

However, a change of the configuration in this way was my original idea. When you get right down to it, it was not that I designed this motif, really I actually designed this blank space. The blank space is more important. I learned to design blank space at the School of Decorative Arts in Paris.

Weisbecker: I wasn’t aware of it. Certainly, my works currently-exhibited at the CLASKA Gallery are a series of buildings, and they are exactly the same. Buildings are drawn by line, and each building is small, but the whole piece is large. The important point here is not buildings, but blank space.

Moriguchi: We can conclude what really has meaning is blank space. Reality exists in the blank space between buildings. The meaning is not found in the buildings…

Weisbecker: Just precisely so. Buildings are an excuse.

Moriguchi: This is a slightly philosophical talk.

Weisbecker: It is surprising that you’re talking about this.

Moriguchi: It is blank space that has meaning.

織田信長が望んだ自由。

制約があり、自由があり、解放がある。

ショッピングバッグで、自由を語る。

The freedom Oda Nobunaga desired.

There are restrictions, freedom, and liberation. Talking about freedom and a shopping bag.

ところで、森口先生は革新という言葉をお使いにならず、「自由」という言葉をおつかいになります。

森口:それを語り始めると非常に抽象的な話になってしまいますので、具体例を挙げて説明させていただきたいと思います。おそらく世界のどこを探しても、布に絵を描いた生地、あるいはプリント生地は、権力者のための衣装ではなかったと思います。権力者、つまり皇帝、王、プリンス、富豪たちは、常に非常に高価な素材で織られた豪華な織物を身につけていました。どの史料や絵画を見ても、彼らの衣装が染め物やプリント地ということは決してありませんでした。どんな王も、常に、非常に豪華で重厚な衣装を身につけていたのです。染め地やプリント地の短い着物を着ているのは庶民だったのです。でも日本は唯一の例外で、絹地に絵を描いた生地の評価が急上昇する時代があったのです。17世紀以降、友禅の技術は、自由を渇望していた江戸時代人の象徴的存在でした。それ以前の日本ではまだ中国・朝鮮文化がかなりの影響力を持って支配していました。当時、朝鮮半島にあった三王朝は、日本に多大な影響を及ぼしていました。茶の湯もそのひとつです。茶道も朝鮮から渡来したものです。16世紀までの日本は渡来した異国文化に席巻された状態でした。そんな中で日本人は異国文化を受け入れつつ、洗練させ、日本化していくわけです。16世紀になると、まさに野生児のような男が現れます。野生児でありながら、非常に知的で、感受性も豊かで、それまでの状況を一新させたいと望んだ男、それが日本の統治をめざした織田信長です。彼は徹底的な変革を望んでいました。手描きの染め物の衣装を身につけ始めたのが彼です。彼はこう言い放ちます。「私は自由が欲しい。ここにしか存在しない一点物が欲しい」。織田信長は、一点しかない物を身につけたいと思い始めたのです。絞り染めです。この時期を機に、日本人の精神が変化していくのです。異国文化からの独立の始まりです。世界各国から文化を取り入れつつも、日本の独創性(オリジナリティ)と自由が第一に求められるようになるのです。16世紀に日本は、日本文化の自立(自主性)を見出し始めるのです。17世紀になると日本は平和な時代に入ります。鎖国時代です。17世紀の半ばには三越が創業を始め、友禅の技術も誕生し、友禅と共に完全に自由な表現が可能になります。それゆえに友禅は、同時期に生まれた浮世絵と同じく、江戸時代が求めた自由のシンボルと考えられるのです。私の仕事について、自由を希求し、新しい道を模索する三越の象徴だと言っていただきました。確かに私も自由の象徴であって欲しいと思っています。ですが、私が選んだ道は一見するとあまり自由には見えないものです。つまりジオメトリー(幾何学)は制約の多いデザインだからです。六角形にしても、正方形にしても、角度にしても、全て完全に定められたものです。

それでも、私が「自由」だと言うのは、自分がどの領域に位置するかを選択する自由があるからです。自分の領域を決めた時点で、私たちは自分が選んだ空間に制限されますが、どこに居場所を置くかを決める自由はあるのです。だから私は「自由」なのです。六角形をひとつ選ぶのも、正方形を3つ選ぶのも私は完全に自由でした。その後に生じる制約は、また素晴らしい制約なのです。最初、模索の段階では試行錯誤もありました。ですが、最終的には、快感、解放感を感じ始めるのです。なぜなら、最初に自分の制約(規則)をうまく選びとったからです。そういう意味での自由なのです。

フランス革命は「自由、平等、博愛」の精神を掲げました。300年以上も前のことです。博愛も平等も自分以外の他者を必要とする概念です。でも、自由だけは他者を必要としません。自分はひとりだと感じることができ、完全に自立できるのです。それこそが私が愛するものです。自由、平等、博愛の中で、自由が一番好きです。

三越の精神と波長が合ったわけですね。

森口:そう少し符合している部分がありますよ。

ワイズベッカー:やや脱線するのを承知でお話しさせていただくと、日本で朝鮮や中国の伝統が普及したというクニの話を聞いて、ひとつ興味を覚えたことがあります。それ自体は素晴らしいことだと思いますが、その取り入れ方に一般的日本人の気質があらわれている気がするのです。日本人には例外なく非常に洗練されたものを感じると、昨日も話していたのです。昨日、そういう話をしていたところに、今日、クニがその話をしてくれた。今、彼が話してくれた日本の歴史を私は知りませんでした。でも、それを聞いて気がつくことは、ある時期、信長ほどの権力者が染め物を身につけ始めた、それによって彼は最上級のランクを下げたとも言えますが、それと同時に社会の底上げをしたとも言えるのです。だからこそ、日本文化にはこれほどの統一感があり、おしなべて洗練されているのだと思います。フランスでは、非常に裕福な人々は豪華なものを所有し、貧民は本当に教養もなければ物ももたないという時代が日本よりも長く続きました。上層階級にとって、失うこと、手放すことが、損失や負けになるのではなく、手放すのは無駄なものであって、その結果、それ以外の階級がランクアップしてくる、そうなるためのほど良いバランス(均衡)を見つけることが必要なのではないでしょうか。

森口:その通りです。

ワイズベッカー:それはとても日本的な現象だと思うんです。

森口:確かに日本は17世紀、下層から上層までどの階級の日本人も皆、陽気でした。厳しい身分制度はありましたが、文化の側面ではとても風通しが良かったのです。そのベースに文学があり、文学の果たした役割はとても大きいと思います。中世文学、平安時代の文学は、庶民、天皇、貴族、領主、分け隔てなく、重要な存在だったのです。こうした文化は非常に特殊です。

ワイズベッカー:そうだね。

森口:第一、こうしてショッピングバッグで自由を語るなんてかなり特殊なことじゃないか。信じられないことだよ。

By the way, Mr. Moriguchi, you don’t use the term “reform”; you use the term “freedom.” Could you expand on that?

Moriguchi: Once I start talking about it, it can get a bit abstract, so let me explain by giving a specific example. As far as I know, nowhere in the world has fabric with drawn or printed pictures been made into clothes for rulers or the wealthy. Powerful figures, that is to say, emperors, kings, princes, and the rich have always worn gorgeous fabrics woven from very expensive materials. When studying any of the historical sources or paintings, their clothes were never made of simple printed fabrics. Kings always put on magnificent and substantial garments to emphasize their power and authority. It was the common people who wore far less elaborate clothes made of dyed or printed fabrics. Japan, however, was the only exception, and there was an era in which the appreciation and recognition of silk fabric with drawn designs suddenly flowered. After the 17th century, the yuzen technique was a symbolic presence for people in the Edo period, who yearned for their own cultural freedom. In earlier Japan, the Chinese and Korean cultures were still dominant and had significant impact; in particular, three dynasties on the Korean Peninsula had exerted a great influence upon Japan. One of the best examples of this effect is the art of the tea ceremony, which was actually introduced from Korea. Japan up to the 16th century was a country easily influenced and susceptible to the introduction of culture from foreign countries. In such circumstances, the Japanese kept accepting and absorbing many new ideas, and over time refined and blended them to create a Japanese culture. It was in the 16th century, when, a man who could be described as a sort of wild man, an enfant terrible of his times, appeared; his name was Oda Nobunaga. Although headstrong, he was also highly intellectual and sensitive, and he wanted nothing less than a revolution. Nobunaga had his eye on ruling all of Japan and he was set to bring about sweeping changes. He was the first person to wear hand-drawn and dyed garments. He bluntly said: “I want freedom. I want a unique thing that only exists here.” Nobunaga wanted to wear bespoke clothes; he demanded haute couture and original one-of-a-kind patterns, such as the exquisite designs created by shibori-zome (tie-dye). Around this time the outlook and mindset of the Japanese people was gradually changing; it was the start of our establishing independence from foreign cultures. Although Japan kept incorporating cultural influences from other countries, there was an increasing emphasis on putting Japan’s originality and freedom first. In the 16th century, Japan began a search for an independent Japanese culture and identity. In the 17th century, Japan entered a peaceful era with an enforced period of national isolation. In the middle of the 17th century, Mitsukoshi inaugurated an enterprise, and the yuzen technique was also born, both of which contributed to the completely free expression and dissemination of yuzen. For that reason, similarly to the ukiyo-e prints that appeared in the same period, yuzen can be considered as a symbol of the freedom so desired by the society of the Edo period.

As for this work I’ve been told that the design perfectly symbolizes Mitsukoshi, and its longing for freedom and the exploring of a new path. Definitely I too want it to symbolize freedom. However, at first glance the path I chose appears not to be so “free,” because any geometrical design naturally involves many restrictions. With hexagons, squares, and angles, everything is pretty much nailed down.

Even so, I still stand by the concept of “free,” purely because I have the freedom to choose which domain I position myself within. When we have decided our own domain, we start to be restricted to the space we have chosen, but we still have freedom to decide where we will be positioned within that space. That is why I am “free.” I was completely free in my choice of one hexagon and the three squares. The restrictions arising later are also wonderful limitations. At first, in the sort of groping stage, I just used trial and error, but in the end I started feeling a pleasant sense of relief, and a sort of liberation, because I skillfully selected my restrictions or framework at the beginning. It is freedom from that sense.

Some 300 years ago the French Revolution heralded the ideals of “Liberty, Equality, and Fraternity.” Fraternity and equality are concepts requiring the participation of others, but only liberty does not need others. I can feel I am alone and can become wholly independent. That is exactly what I love. From among liberty, equality, and fraternity, I like liberty the most.

That means you and Mitsukoshi’s spirit were on the same wavelength, right?

Moriguchi: Yes, there is a part where we see eye to eye.

Weisbecker: If I could just return to when Kuni mentioned that Korean and Chinese traditions were spread in Japan, this really piqued my interest. I think such a movement was wonderful; however, I feel that the way the ordinary people incorporated such different cultural influences is a reflection of the Japanese temperament. Yesterday, I was saying that without exception I feel something very sophisticated about Japanese people. Only yesterday, I was saying that sort of thing, and now today, Kuni is saying the same sort of thing as well. I didn’t know those aspects of Japanese history he has just explained, but after listening to him, what I have noticed is that at one period, such a powerful man as Nobunaga started wearing dyed garments; it can be said that by acting in this way, he in effect lowered the highest ranked in the land, but it can also be said that in the same instant, he raised the level of all society. Precisely for this reason, to a large extent Japanese culture is endowed with a sense of unity, and on the whole it is pretty refined. In France, we had many centuries where very wealthy people possessed extraordinary luxury, and poor people were ill-educated and possessed very little, and this period lasted longer than in Japan. For the upper classes, to lose and to let go does not mean loss or defeat, rather what is let go is simply waste, and as a result, the other classes will be ranked higher; I think there is a need to find a proper balance to realize this.

Moriguchi: That’s right.

Weisbecker: I think it is a very Japanese phenomenon.

Moriguchi: Certainly, in 17th century Japan, Japanese people at all levels of society were basically cheerful. Although there was a strict class system, on the cultural side, there was a good open atmosphere. At its base we find literature, and in my view literature played a significant role. As subjects in medieval or Heian period literature, there is no discrimination between commoners, emperors, aristocrats, and feudal lords, and literature was very important for their life. Such a culture is very distinctive.

Weisbecker: Yes it is.

Moriguchi: In the first place, it is very special to talk about freedom in this way and particularly when it’s connected with a shopping bag; it’s a bit hard to believe.

過去を紐解き、現代を見つめ、

これからの姿を探る。

21世紀の視点で伝統を表現する。

Study the past, observe the present,

and explore our future direction.Express tradition from the viewpoint of the 21st century.

森口:三越が果たすべき役割があるとすれば、これまでの過去の功績を忘れてはならないと同時に、今はどういう社会であるかをよく見極める必要があると思います。そうすればおのずと答えが見つかるのではないでしょうか。三越が対象にしているのは多くのお客さまです。ひとりひとりが考えるべきで、それが力になると思います。このデザインを通した私と三越のコラボレーションの試みも、これもひとつの方法でしかありません。象徴的なものです。おそらく三越は明治・大正時代に日本の近代化に大きな役割を果たしたと思います。この過去に果たした功績を忘れてはならないと同時に、そこに留まっていてはいけないのです。なぜなら世界は常に進化しているからです。

ワイズベッカー:そうです。先ほども少し説明させていただきましたが、大切なのは、伝統の素晴らしい部分を尊重する精神を守りつつ、21世紀の視点でもってその伝統の良い部分を表現することです。やみくもな、とにかく変えなきゃいけないから変えるという方法は、良い解決方法ではありません。

森口:そう、良い解決法ではないですね。長続きしないでしょう。フィリップ、とにかく今日は時間をとってくれてありがとう。疲れてないかい。

ワイズベッカー:僕はクニとならまだまだ何時間でもしゃべれるよ。本当の親友だからね。僕らは波長がぴったりなんですよ。

森口:そう、おしゃべりだけで時間がもつ。ビールがあればもっといいかな(笑)

Moriguchi: If there is a role to be fulfilled by Mitsukoshi in the future, Mitsukoshi must first never forget its past achievements, while fully grasping what kind of society we live in today. If Mitsukoshi follows this, I think the company can naturally find the answer. Each employee of Mitsukoshi deals with many customers, and all of them need to spend time thinking about their expectations and the issue of the company’s role; I believe this will develop their strength. This collaboration with Mitsukoshi through my design and their bag is just one approach, which is something symbolic. In the Meiji and Taisho eras, Mitsukoshi can be said to have played a great role in the modernization of Japan. These great achievements of the past must not be forgotten and at the same time, they must not hold us back, because the world always keeps evolving.

Weisbecker: Yes. As I said a little earlier, the important point is to express the best part of tradition from the viewpoint of the 21st century while preserving the spirit that respects the best of our traditions. It is not a good solution to act just randomly, or change any old way simply because we must change anyhow.

Moriguchi: No, it isn’t. It would not last long. Philippe, anyway, thank you very much for taking time to be with us today, don’t you feel tired?

Weisbecker: With Kuni I can still talk on for hours, as you are my true best friend. We are perfectly tuned on the same wavelength.

Moriguchi: Yes, we can spend time just chatting, but it might be even better with a beer or two. (Laughter)

※森口邦彦氏の「邦」の異体字は、ブラウザで正しい表記ができませんこと、ご了承ください。

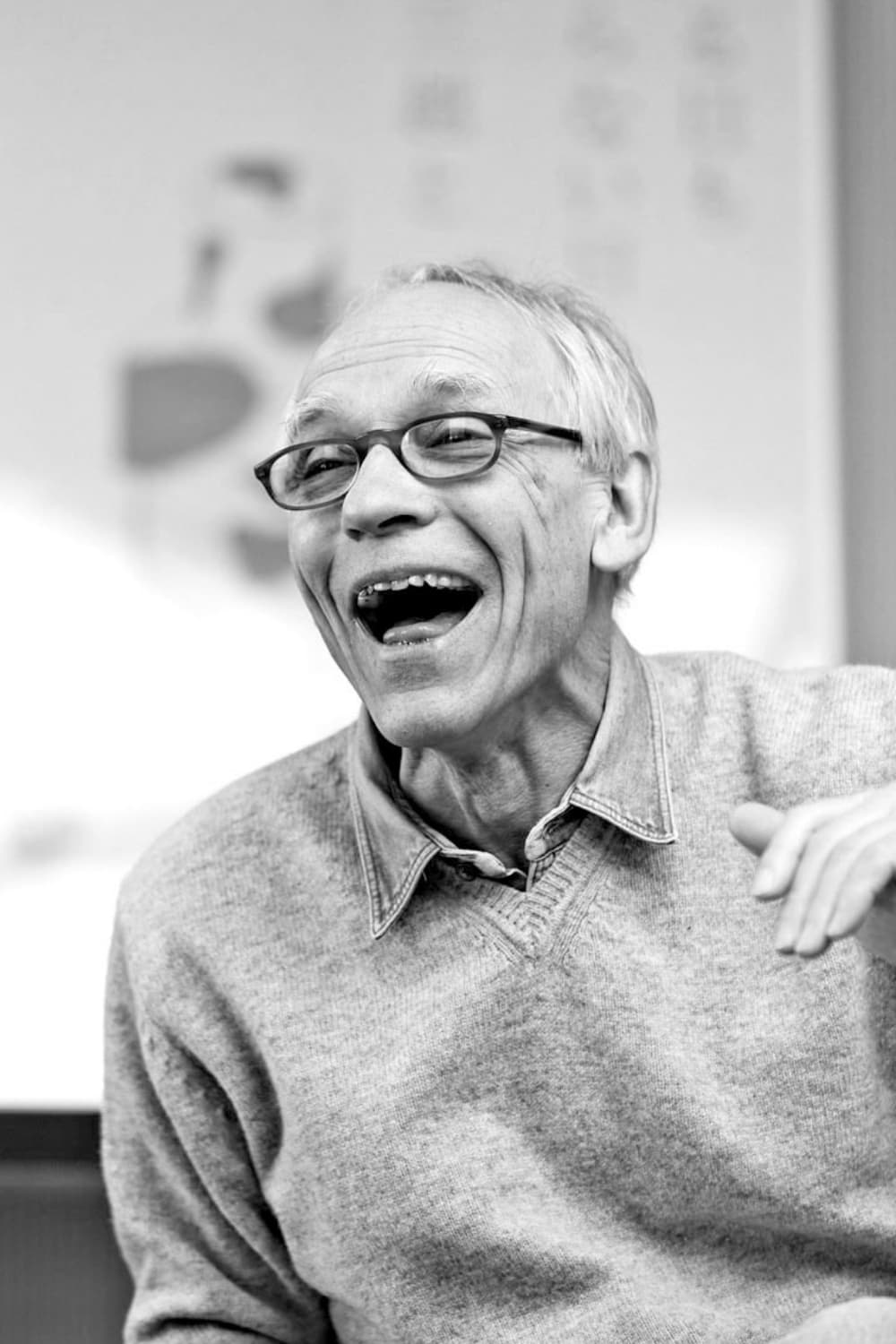

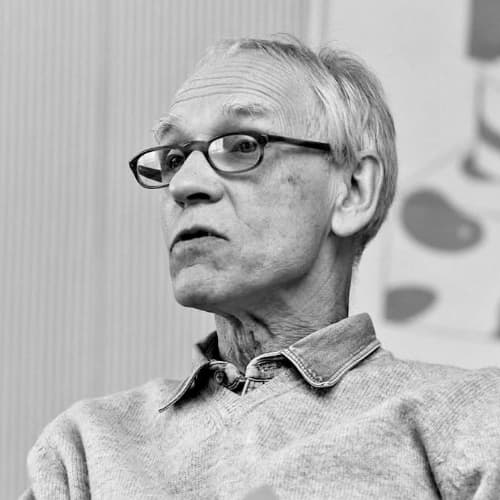

フィリップ・

ワイズベッカー

Phillippe Weisbecker

1942年生まれ。1966年フランス国立装飾美術学校卒業。1968年にニューヨークに移り、アーティスト、イラストレーターとして活動を始める。現在はパリ、バルセロナを拠点に活動。日本でも展覧会や広告、作品集の仕事を手掛け、JAGDAや東京ADCなど受賞。2014年9月にはニューヨークで大規模な個展の予定。

Born in 1942. After graduation from the French National School of Decorative Arts in 1966, Philippe moved to New York in 1968, and started his career as an artist and illustrator. At present, he is based in Paris and Barcelona. In Japan, he has held exhibitions, carried out commissions for advertisements and collections of works, and received awards from JAGDA and Tokyo ADC.** In September 2014, he will hold a large-scale solo exhibition in New York.

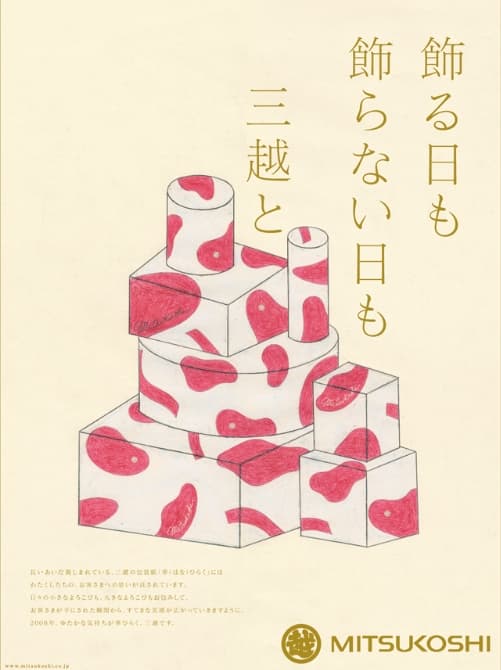

2008年にワイズベッカー氏が手がけた三越のポスター